There is much hope in the land for the New Year; 2020 will not be fondly remembered by most people. I do not have to detail the collective tragedy of this lost year. On the positive and personal side, we were blessed with two healthy new grandsons this year, but have only seen them once. And, just as the vaccine is in our sights, Covid has surged. It has even entered my immediate neighborhood for the first time.

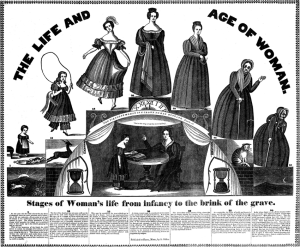

I have written in another year about the images of the “old” year (Father Time) and the “Baby” New Year. This is a holiday which will not let us forget time is passing. As I get older, New Year’s Eves come faster and faster, and I go to bed earlier and earlier. No bells at midnight for me. And I am cognizant today that 2021 is the year in which I will turn 70. Seventy seems old to me. I am sure I will get used to my new decade (although my husband who is two years ahead of me says he hasn’t). But the numerical marker is a bellwether, a harbinger of things to come.

The Bible tells us that seventy years is all we can expect of life. Psalm 90 is quite explicit on this point:

The days of our years are threescore years and ten; and if by reason of strength they be fourscore years, yet is their strength labour and sorrow; for it is soon cut off, and we fly away.

Or in a more modern translation:

Seventy years is all we have—eighty years, if we are strong; yet all they bring us is trouble and sorrow; life is soon over, and we are gone.

One can argue that in Biblical times 70 was much older than it is now. Maybe. But I know there are many things about old age that have not changed, that cannot be easily “cured,” including the simple truth of the wear and tear our bodies and minds have undergone for seven decades.

As anyone who has been reading these blogs will know, there has been much debate in recent years on what our attitude toward old age should be. One of my favorite authors (both as the academic Carolyn Heilbrun and the mystery writer Amanda Cross) wrote The Last Gift of Time – Life Beyond 60. It is a lovely book about getting older and delineates many of the joys of old age. Yet, Dr. Heilbrun also vows in the book to commit suicide at age 70, as “there is no joy in life past that point, only to experience the miserable endgame.” She actually waited until she turned 77; I wish she had waited longer.

A few years back (2014), Ezekiel Emanuel (noted oncologist and bioethicist who was recently appointed to Biden’s Covid team and whose brothers are Rahm and Ari) wrote a much-discussed article in The Atlantic entitled “Why I Hope to Die at 75.” The title is misleading; Emanuel does not necessarily hope to die in his mid-seventies. But he has decided that by age 75 he will give up all measures to make him live into a very long but perhaps debilitated old age. He is clearly against euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide, but:

I am talking about how long I want to live and the kind and amount of health care I will consent to after 75. Americans seem to be obsessed with exercising, doing mental puzzles, consuming various juice and protein concoctions, sticking to strict diets, and popping vitamins and supplements, all in a valiant effort to cheat death and prolong life as long as possible. This has become so pervasive that it now defines a cultural type: what I call the American immortal.

I recommend the article – particularly those parts about where our health care dollars are going and how statistics show that longevity improvements often just “increase the years spent in disability.” By the way, Dr. Emanuel says in this essay that he will no longer take flu vaccines after age 75; I wonder how he feels about this in the current situation. I do not want to make his argument simplistic though; it is a powerful statement of reality in the face of the very unreal chase after immortality. As I approach my eighth decade, all these things are on my mind.

This is my last post in a remarkable year. It is also the time for printing up my journal for the month of December and completing the three-ring binder labeled 2020. This is the 17th year I have undertaken this process of recording my life in an organized way; these piles of words remember more than I do. Virginia Woolf said, once, that she wrote her diary for her 50-year-old self to read (she was in her thirties when she said this). Why does a 70-year-old keep a diary? (I bet you know the answer to this – if not read my blog on the subject here.) And when is it time to stop writing and just to review and reflect?

December 31st is also time to put away my books of morning readings – this year it was readings from C.S. Lewis and the third volume of a set of daily poems that I cycle through on a triennial basis. It is a time to start clearing away Christmas decorations and throwing out old calendars.

And, as we clear away the old, are we getting ready for that final clearing away? Does the end of a year make us consider that – perhaps – the new year might be our last? Out with the old, in with the new? Old man time being replaced by baby new year? The old year being shuffled into drawers, shut into binders, or collected in folders for our tax returns? I have made no resolutions for the New Year. I am not as pessimistic as Carolyn Heilbrun or Ezekiel Emanuel, but I did watch my mother’s life disintegrate into a malicious form of dementia in the end. There should be some middle ground to this business of fading out, of becoming someone we don’t recognize mentally or physically. I have no answers, but am open to alternatives. And, in truth, I look forward to this new year. Especially, to this new year.